Carved from discarded or naturally shaped wood, Koppabutsu are modest Buddha figures that capture something much greater than their humble appearance suggests.

They are spiritual objects rooted in nature, tradition, and imperfection—each one unique, personal, and full of quiet power.

This article explores the historical roots of Koppabutsu, the philosophy of modern sculptor Sho Kishino, and a personal reflection linking these figures to Gaou, a haunting character from Osamu Tezuka’s manga “Phoenix”.

What Is Koppabutsu? – Humble Devotion in Wood

The term Koppabutsu comes from “koppa,” meaning wood scrap or chip. These Buddha figures are often carved from leftover wood—sometimes just a branch, a sliver, or a block—without trying to force them into idealized forms.

The carver allows the shape and grain of the wood to guide the process. What emerges is not perfection, but authenticity: a spiritual presence within the material itself.

Koppabutsu has deep historical roots in Japanese Buddhism, most notably through the 17th-century monk Enku, who is said to have carved over 120,000 Buddha figures during his lifetime.

He traveled across the country, carving Buddhas out of whatever wood he found and giving them to people in need of spiritual comfort.

His works were raw, direct, and deeply emotional—qualities that continue to influence Buddhist folk art to this day.

Sho Kishino’s Living Tradition

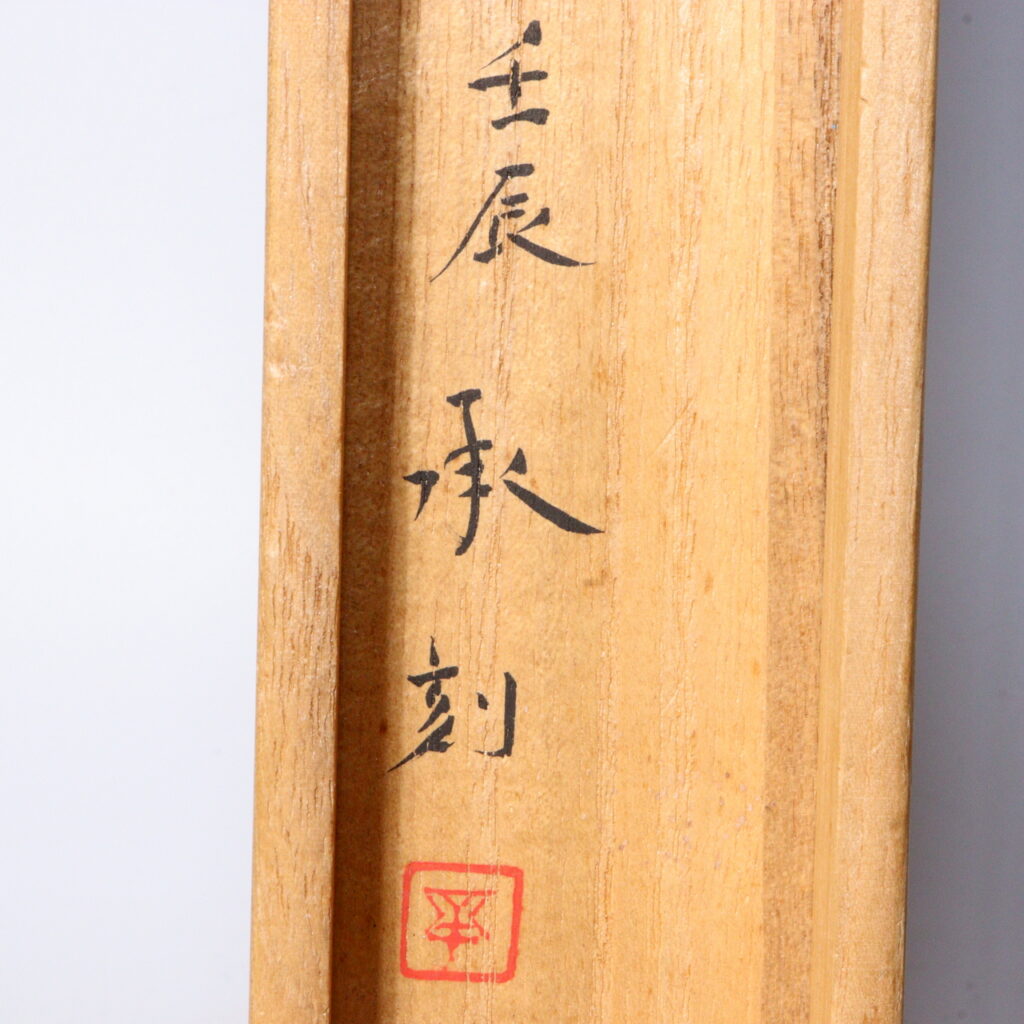

Contemporary sculptor Sho Kishino honors and revitalizes this tradition with his deeply spiritual works.

Rather than approaching wood as a medium to be conquered or shaped into beauty, Kishino listens to it. He allows the grain, the cracks, and the imperfections to remain, believing that the Buddha already resides in the wood, waiting to be revealed.

Kishino’s works often appear weathered, fractured, or asymmetrical—but that is precisely where their strength lies.

They reflect the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi: the beauty of imperfection, impermanence, and humility.

His sculptures do not attempt to replicate historical forms or refined styles; instead, they feel like companions—silent, grounding, and alive.

Meditation and Koppabutsu – A Personal Reflection

Through my own practice of Vipassana meditation in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, I’ve come to value silence, presence, and awareness.

The practice of sati—mindful attention to breath, body, and thought—has guided me through stress, uncertainty, and inner turmoil.

It is a way of returning to the present moment, again and again, with openness and equanimity.

When I encounter a Koppabutsu, especially one carved by Kishino, I often recall moments of meditation.

The statue stands without force or flourish. It doesn’t demand attention—it simply is.

That stillness, that unshakable presence, is what I also find in moments of deep concentration.

In this way, these statues are not merely visual or tactile—they are meditative spaces in themselves.

Their surface—weathered, silent, broken—is a mirror for our own hearts.

They remind me that peace is not perfection. It is acceptance.

And in that acceptance, there is strength.

Gaou and the Carver’s Redemption – A Parallel in Art

This feeling also brings me back to Gaou, a tragic figure from Osamu Tezuka’s “Phoenix”.

Once a violent man whose life was shattered by pain and rage, Gaou finds redemption in sculpting Buddha figures.

His hands, once destructive, become tools of compassion.

Though blind and broken, he carves Buddhas from memory, from spirit, from need.

Gaou’s Buddhas are not beautiful by classical standards. They are rough, unfinished, and flawed—yet filled with life.

They contain sorrow and hope in equal measure.

In them, we see not religious icons, but reflections of suffering transformed.

And in that transformation, they become sacred.

For me, Sho Kishino’s works carry the same quiet urgency as Gaou’s:

to bring forth something honest, flawed, and full of spirit from the silence of wood.

They ask nothing. They demand nothing. But they hold space for healing.

Why Koppabutsu Matters Today

In an age of noise, distraction, and polished surfaces, Koppabutsu offers something different—something necessary.

Each piece is a reminder of the beauty in imperfection, the dignity of aging, and the presence of spirit in all things.

They bring us back to the essence of Buddhist practice: attention, compassion, and humility.

Whether displayed in a meditation corner, on an altar, or simply held in the palm of one’s hand, a Koppabutsu is not just art.

It is a companion on the path.

A gentle, silent presence that reminds us who we are, and how deeply we are held by the quiet things.